“Stay Gold Ponyboy, Stay Gold.”

Thesis Proposal

By: Dawn Stechschulte

INTRODUCTION:

“You are Mr. or Ms. Everyone, since everyone is an art lover to some extent. So, you are in love. And just as you need no theory of woman to love a woman, or of man to love a man, you need no theory of art to love art. Just as no one falls in love with Woman (or Man) in general, no one falls in love with Art in general. Even Don Juan, who is looking for

the woman, loves women individually, one by one. You are in love with this or that work, and certainly with more than one at a time, but not with all works. Like your choices in love affairs, your choices in art are free and at the same time compulsive. Something irresistible attracts you. You don’t always know what, but you know that you are attracted because you feel it. All you have for knowledge is your own certitude and all you have for certitude is your own feeling. To you it is indisputable; it is its own proof. Your friends, your psychoanalyst if you have one and you yourself might be endlessly suspicious of this feeling; your social milieu might disapprove of it; the establishment might repress it or forbid its expression. All this would make it more exalted or painful, but would take nothing away from its authenticity. In love affairs, with works of art as with people, your feelings are of course determined by past experience, channeled through the story of your family, conditioned by your belonging to this or that social class, by your sex and your gender, by your education, by your heredity. Obviously, you can only love within the limits of your social determination and of the cultural opportunities that are objectively available to you, but that doesn’t stop you from loving.”

[1]

Nostalgia is subsequent to the experience of emotion, Thierry de Duve’s description of how love comes about offers a context and proposition of how nostalgia might originate: “your feelings are of course determined by past experience, channeled through the story of your family, conditioned by your belonging to this or that social class, by your sex and your gender, by your education, by your heredity.” The majority of my own nostalgia is derived from love, or a sense of longing to re-remember the past. Most recently my grandmother and I have been writing letters back and forth; specifically we’ve been talking about our family history.

From 1939 to 1945 my Grandfather, Jack Winchester, was abroad in Asia and Europe fighting during World War II. Every year when he came home to visit my Grandmother would get pregnant; they had a total of six children during the duration of the war. Throughout this period my Great Great Aunt Lena, Magdalena Bernadette Kaminski, moved in with my Grandmother to help her raise the children. My mother always referred to Aunt Lena as a spinster, with so many children to take care of she never got the opportunity to get married or have children of her own. This is just a portion of my history, one that is documented through letters and photographs.

“The Future Of Nostalgia” by Svetlana Boym reinvestigates nostalgia: “In my view, two kinds of nostalgia characterize one’s relationship to the past, to the imagined community, to home, to one’s own self-perception: restorative and reflective. They do not explain the nature of longing nor its psychological makeup and unconscious undercurrents; rather they are about the ways in which we make sense of our seemingly ineffable homesickness and how we view our relationship to a collective home.”

[2] Boym defines restorative and reflective as tendencies of nostalgia, restorative puts more emphasis on

nostos (Greek word for homecoming) by patching up the memory gaps through rebuilding the lost home, while reflective puts focus on

algia (

algos is a Greek root meaning pain or longing) by longing for a past that is irrevocable.

“Stay Gold Ponyboy, Stay Gold” will encompass what I want to re-remember and re-read by diving into my own personal amnesia and collective memory. The show will be an installation of multiple (5 to 8) different projects that are linked through the residue of communication, examples are: photographs, letters, and voicemail messages. My intention with this show is for the viewer to find “punctum”; to be pricked by what describes my past, they will be pushed by that moment to reflect upon their own personal histories and their own relationship to nostalgia. “Stay Gold Ponyboy, Stay Gold” will ask the viewer to contemplate how they perceive and document nostalgia, by asking them to look back and reflect on their own personal and collective memories, as well as to look forward to the new ones that have yet to happen. This will happen by exposing what it is that I do to recall my own personal history -- to love, to hate, to experience life and not just study it. This will entice the viewer to look back and reflect on their own personal and collective memories, as well as to look forward to the new ones that have yet to happen. My intention is to create an intimate relationship between the viewer, my own personal narrative, and their personal history; thus creating a new interaction, a new memory. I’m interested in provoking questions such as: What makes me feel nostalgic? As a society should we rely on history to document and remember our collective memories? Why is it important for us to record our personal memories?

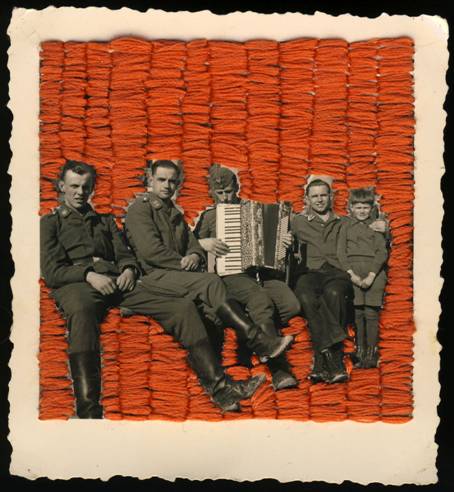

“And If You Didn’t Know It Already, I Love You” is a new project that was inspired by my Grandmother’s role, as a wife and mother, during World War II. When my Grandfather was away at war my Grandmother would embroider, quilt, and sew clothing for the children with Aunt Lena, she said it helped to make the time go by more quickly. Responding to my Grandmother’s stories, I started bidding on eBay for World War II love letters and photographs of soldiers; once I read the love letters I began to stitch into the photographs removing their specific context. The letters expressed a desire for the war to be over, for the authors to be in a different time and a different place, and the photographs were a reminder that none of that was true. By stitching out the background I have “removed” the war as well as the context of the individual soldiers displacing them into a blank space.

A common link between every war we experience is an overwhelming sense of longing that comes from the displacement of the soldiers and their loved ones. The intention of this project is to reflect upon longing caused from such displacement. What is our relationship to war? Who do we know that have been impacted by it? Can we imagine what it would be like to be displaced from your home, family, and friends? What would we do to keep from missing them? This project invokes the tendencies of reflective nostalgia because I am asking the viewer to remember an irretrievable past that can only be reflected upon; thus evoking individual and cultural memory.

“And If You Didn’t Know It Already, I Love You.”, 2 ½ X 2 ½ inches, photo and thread.

A majority of my work is influenced by the Fluxus; two methods are distinctive to Fluxus: a type of performance art called the Event, and the Fluxkit: everyday objects or printed cards collected in a box that viewers explore privately. Many Fluxus works evolve over extending periods, this is obvious in the Fluxus performance works: musical compositions lasting days or weeks, performances that take place in segments throughout a year, or art works that grow and evolve over decades. Fluxus is an artistic philosophy; it is an attitude towards art and life.

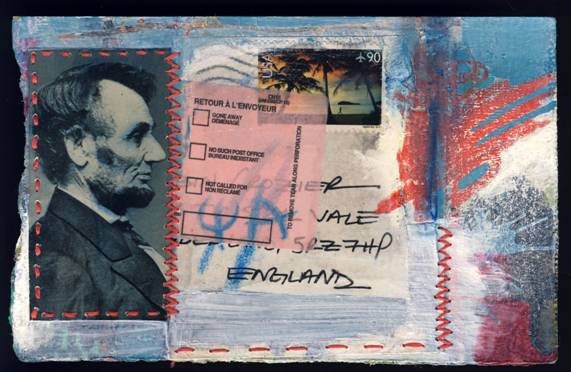

Fluxus artists also associate with the amorphous mail art network that involves thousands of international participants. A saying among mail artists is "senders receive," meaning for you to receive mail art you must send it as well. The project “Forget Me Not” utilizes the strategies employed by the genre of mail art; specifically it’s an ongoing collaborative long distance mail art project with fellow Seattle artist Marcie Myrick. Throughout undergrad, at Cornish College of Fine Arts, Marcie and I collaborated. When I moved away to attend graduate school, at Ohio University School of Art, we used mail art as recourse to the distance. Communication is the vehicle that establishes and documents this longing and displacement. Somehow talking on the phone wasn’t enough; specifically that wasn’t how we wanted to communicate with each other. The project “Forget Me Not” is quite simple: we both make postcards and send them to each other in packages of twenty, then we respond to what it is that the other has done and pop it in the mail. The postcards are intuitively made with found bits and pieces (lists, receipts, tickets, etc.) collaged with prints and paintings that were “errors”. “Forget Me Not” reiterates how much Marcie and I miss each other, as well as our need to collaborate with each other. There will be over one hundred postcards that will be displayed on shelves that will entice the viewer to find the “punctum” yet again, that through the handling of and reading of these private correspondences that they reflect upon their own personal relationships. A pile of postcards will be made for the viewer’s free use, what happens to the postcard will be up to them; they can keep the postcard as a souvenir, or send it to a friend, family member, or possibly them self. This encouraged participation is intended to incite the audience to begin their own processes of documenting their own personal histories.

“Forget Me Not”, 4 X 6 inches, mix media.

SIGNIFICANCE:

Andre Codrescu is a poet, novelist, essayist, and commentator for NPR; specifically he is interested in critiquing the historical amnesia in America. “Nobody can remember a damn thing! Every time somebody adds memory to their machine thousands of people forget everything they knew. Americans are singularly devoid of memory these days. We don’t remember where we came from, who raised us, what our wars use to be, what happened last year, last month, or even last week. School children remember practically nothing.” As a culture are we disassociating from our histories? What would our world be like without nostalgia, what if no one ever longed to return home? How are remembering and forgetting intertwined? Is sentimentality a burden because it requires us to look back, or does it keep us from looking forward? I can’t help but to think of these questions when I find large lots of family photos on eBay disconnected from any kind of personal narrative. Is eBay the place in which all this information could sediment? Are people vigorously disposing of keepsakes of memory to disengage with nostalgia? Has technology changed the way that we remember?

Psychologist Elizabeth Loftus has spent more than twenty years studying human memory. Her experiments focus on how a memory can be changed by things that we experience; specifically we alter our memories because our imagination is so vivid it makes them up – memory is malleable. The more you remember something the more it becomes about you and less about it happening, every time you’re remembering you’re re-remembering, thus every time you remember something you’re changing it a little. Without knowing it, we adopt memories and take them as our own, constructing experiences that never really happened; an example might be how history is mediated through technology. Advancements in technology allow us to watch the news rather than read it, connecting with our history on a much more immediate, personal, and yet potentially fictional level – as if we were there. Certain generations will always remember watching the explosion of the Challenger, the attack on 9/11, or Hurricane Katrina because as a society most experienced it by watching it happen “live” via TV, thus creating a collective memory through technology.

The attack on 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina were both so recent that I can remember them very vividly, but I couldn’t recall what the explosion of the Challenger looked like, so I looked it up on YouTube. If we want to re-remember we can go to YouTube and re-experience it because our memory isn’t reliable. Is technology as invasive as Andre Codrescu expresses, “Every time somebody adds memory to their machine thousands of people forget everything they knew”? If we know that after a certain amount of time passes we won’t remember as clearly, then what’s wrong with relying on technology to do the remembering? Do we not trust technology?

The great eighteenth-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant famously categorized the sentiment as “pathological”, maybe he knew the more we remember the more we forget? Nostalgia and sentimentality are derived from, or reliant on, remembering; both are secondary to love or emotion. What remains unclear is how passion and emotion fit in with ethics and moral philosophy, or even how we are suppose to understand them? In Defense Of Sentimentality, Robert Solomon explains why Kant felt sentimentality was to be avoided when it comes to right and wrong: “It was Kant who argued so fervently against reliance on the ‘inclinations’ in moral matters, insisting instead that all evaluations of ‘moral worth’ should rely on obedience to principles and practical reason rather than having the right feelings or displaying a proper character. Emotions, according to Kant, were too capricious, too easily shifted, to readily influenced by other people. Emotions, unlike reason, differed from culture to culture, even from person to person.” (Robert C. Solomon, In Defense of Sentimentality, pg. 28) The expressive sentiment will never be accepted by the unemotional reason; certainly sentimentality will always be rejected as a mere reaction.

METHOD:

I don’t trust my memory. I’m afraid it won’t remember all the experiences that structure my personal history; through writing, collecting, and art making I create the mementos, or souvenirs. These objects are given or kept as a reminder of, or in memory of, somebody or something. Decisions on process are based on specific content; an example might be the stitching in the photographs, “And If You Didn’t Know It Already, I Love You”, the thread is intended to remind the viewer of embroidery -- a reference to my Grandma, or the “feminine touch”. The photographs and the stitching lead the viewer closer and closer to the narrative that I want them to experience; specifically invoking nostalgia or at the very least memories of whomever they know or knew that was impacted by the war.

Beyond my choices in medium, the method of how the work comes about is also very important. “And If You Didn’t Know It Already, I Love You” is an art project that was inspired by the letters my Grandmother and I have been writing to each other. Collaboration is the vehicle that drives my work; when the viewer handles the artwork, sends the postcard, or reflects on a personal memory they participate with the project, if only even casually, and in doing so they generate new letters of correspondence.

The strategies that I will employ to create this work will focus on collaborating, collecting, collage, and remembering. Some projects will have specific rules or guidelines that will help guide the project towards a specific outcome, for the viewer to find “punctum”. In being a controlled study I can direct attention towards reflective and restorative nostalgia; on the other hand some projects will be intuitively guided by my personal histories, correspondences, and longings.

[1] Thierry de Duve,

Kant after Duchamp, 31-32.

[2] The Future Of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym, 41.